Hamer’s words resonate today, as the fight for voting rights for Black Americans and other marginalized groups continues. Hamer’s eight-minute plea ended with a haunting question: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where…our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

She described how police beat her brutally, just for trying to teach other people how to register to vote.

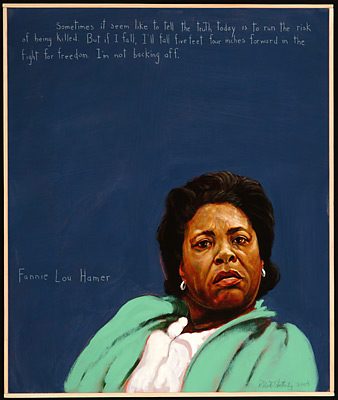

Marlow, evicted her from the land she farmed and the home she shared with her husband and daughters-simply because she tried to register to vote. Her voice rose as she recounted virulent racism and state-sanctioned terror. Two male colleagues had already read prepared statements, to little response from the audience Hamer’s speech buzzed with authentic personal and emotional experience, and it stole the show. She sat at a witness table, the committee chair behind her, stared down by 100 rank and file members and nearly 200 spectators and reporters. Hamer was not the typical face of the growing movement, dominated by elite men and youthful radical activists, but a Mississippi Delta cotton picker with a sixth-grade education.

That August, she testified before a convention committee, alongside better-known civil rights activists, including Martin Luther King Jr., and demanded the right to represent the citizens of Mississippi as a party delegate. Now, adding to their disenfranchisement, white Southern Democrats were proposing seating an all-white delegation at that year’s Democratic National Convention.įannie Lou Hamer-a poor, middle-aged, Black sharecropper-wasn’t having it. Though Black people represented 50 percent of Mississippi’s voting age population in 1964, Jim Crow literacy tests, poll taxes, violence, and intimidation had managed to all but silence their political power at the polls.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)